A Series of Revelations

In 1988, during production of the Famicom, Nintendo manufactured floppy disks for the Disk System, a peripheral that used

proprietary floppy disks to play games with more sophisticated sound. It was around that time that they started work on a 16-bit

successor to the Famicom, called the Super Famicom. But one day Ken Kutaragi, engineer of consumer electronic and semiconductor

company Sony, watched his daughter play video games on the Famicom they had at home.

He then instructed Sony management to design and manufacture an SPC-700 sound chip, and demonstrated it to Nintendo, who

used it in their upcoming console. This gave Kutaragi an opportunity to show his team could fulfill his aspiration of developing

a powerful gaming system, having realized that game consoles were the most popular home entertainment systems and CD-ROM

technology would one day make cartridges obsolete due to being cheaper to manufacture and able to store way more memory.

Kutaragi steering the company in this direction nearly cost him his job, as Sony HQ felt video games flew in the face of their

sophisticated consumer electronics brand. He did have the support of executive Norio Ohga, allowing the project to continue.

After a little bit of convincing, Sony did warm up to it, realizing they can gain more ground in the rapidly-growing video game

market, having been manufacturers of the Japanese MSX computer in the past.

A Series of Visions

Next, Ken Kutaragi instructed management to build a CD-based peripheral for the Super Famicom.

Nintendo didn't agree but allowed Sega to continue working on the drive.

That would be a home entertainment system that played SNES games and new Sony-manufactured "Super Disc" CDs, which they would

design. The agreement gives Sony the international rights and a lot of control over the games under the new format, despite

Nintendo reigning in the video game market. Sony was adamant in obtaining a music and film license so their new console can play

movies and CDs, which would make them the only company of the pair to actually benefit from the license.

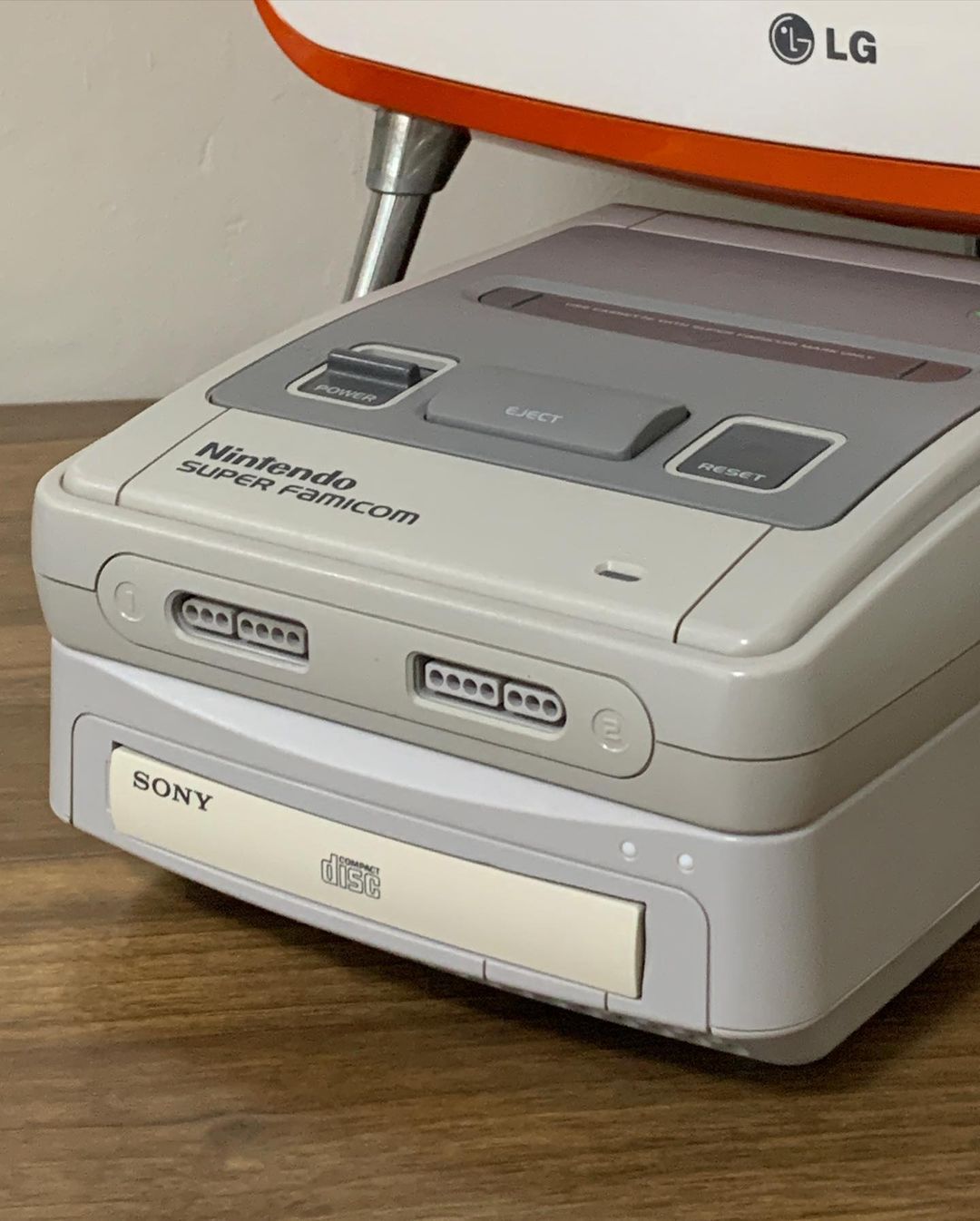

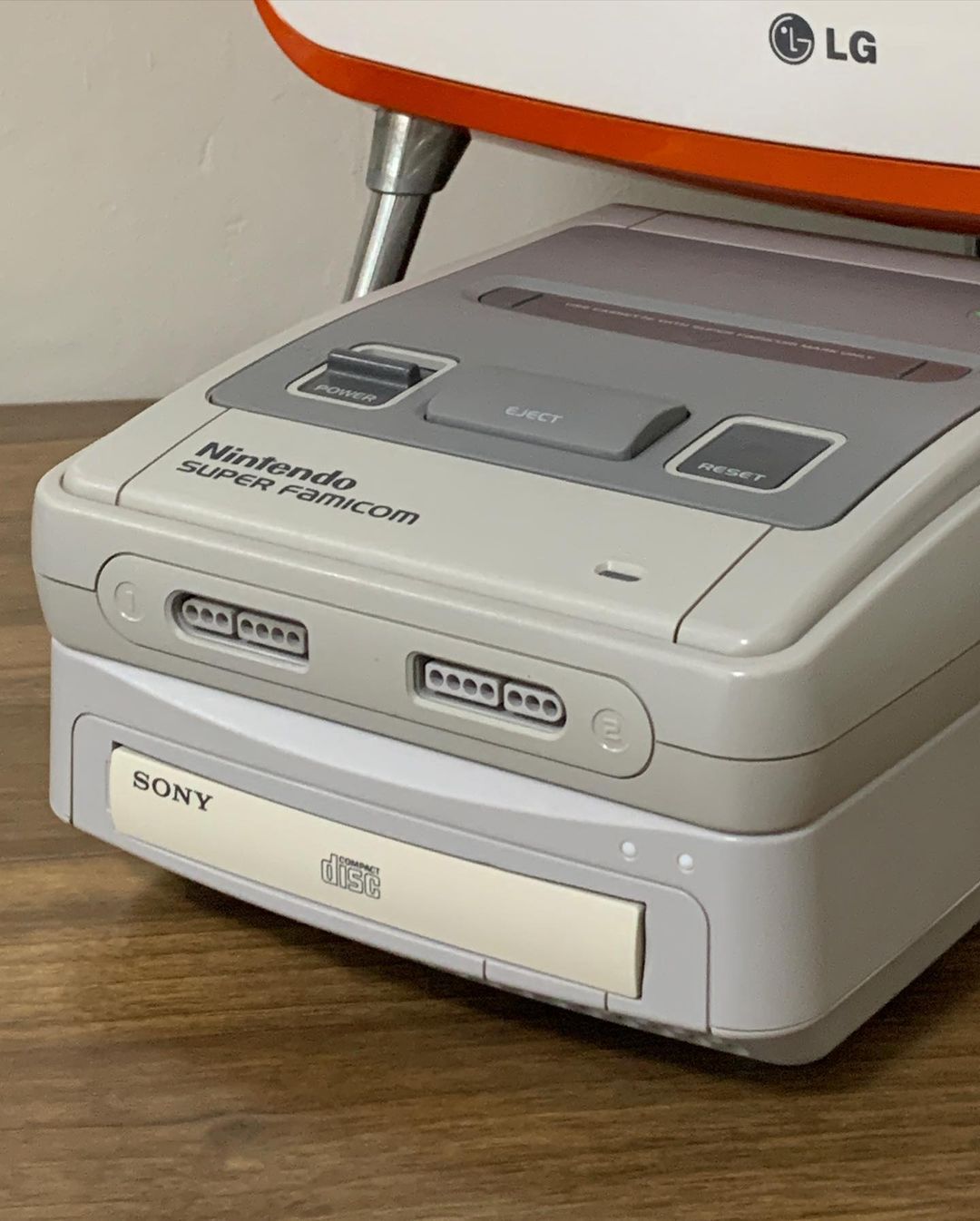

The deal that resulted was for the production of two different systems: one was a CD-ROM peripheral for the SNES (think the Sega

CD for the Genesis), and the second was an all-in-one console that played SNES cartridges and CD-ROM games, called the

PlayStation.

The Standup

The "Play Station" (two words at the time) was to be announced at the 1991 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. However,

Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi worried about the advantages Sony had over them, like their superior research and development

department and aforementioned music/film license letting Sony dictate SNES-CD game design. So without warning, to protect

Nintendo's own licensing structure, Yamauchi cancelled all plans for the peripheral. He then sent Nintendo of America's president

Minoru Arakawa and chairman Howard Lincoln to Amsterdam to create a "more favorable" contract with Sony's rival Philips, so

Nintendo could take control of the game licenses on Philips-branded machines. Two days before CES, Sony director of public

relations Nobuyuki Idei and chairman/CEO Ken Kutaragi found out. Despite all this, Nintendo and Sony were still negotiating

another deal, wherein the Play Station would have an SNES game port and Nintendo could keep most of the profits and rights, as

long as Sony's SPC-700 sound chip is still used. But on day one of CES, they still announced their partnership with Nintendo on

the Play Station. Only the next morning did Sony find out when Lincoln stepped on stage to announce their partnership with

Philips, also blindsiding the audience.

The Solo Way Forward

Ken Kutaragi insisted Sony stay in the gaming industry. Understanding that action was needed, they and Nintendo severed ties on

May 4, 1992. Ohga called a meeting in June to determine the next move with the PlayStation project. When Kutaragi showed a

CD-based system he secretly developed which played games with 3D graphics, some executives opposed it as they felt the gaming

industry was "culturally offbeat" and Sony should stay in the audiovisual industry where companies knew each other well and made

civilized business decisions. Ohga decided to continue the project, building upon what the partnership got them thus far and

made an SNES-based console alone. They had no experience in game development, so they relied heavily on third-parties to develop

games. Eventually, Sony released it as a standalone console as the "PlayStation" on December 3, 1994.