A Titan in the Making

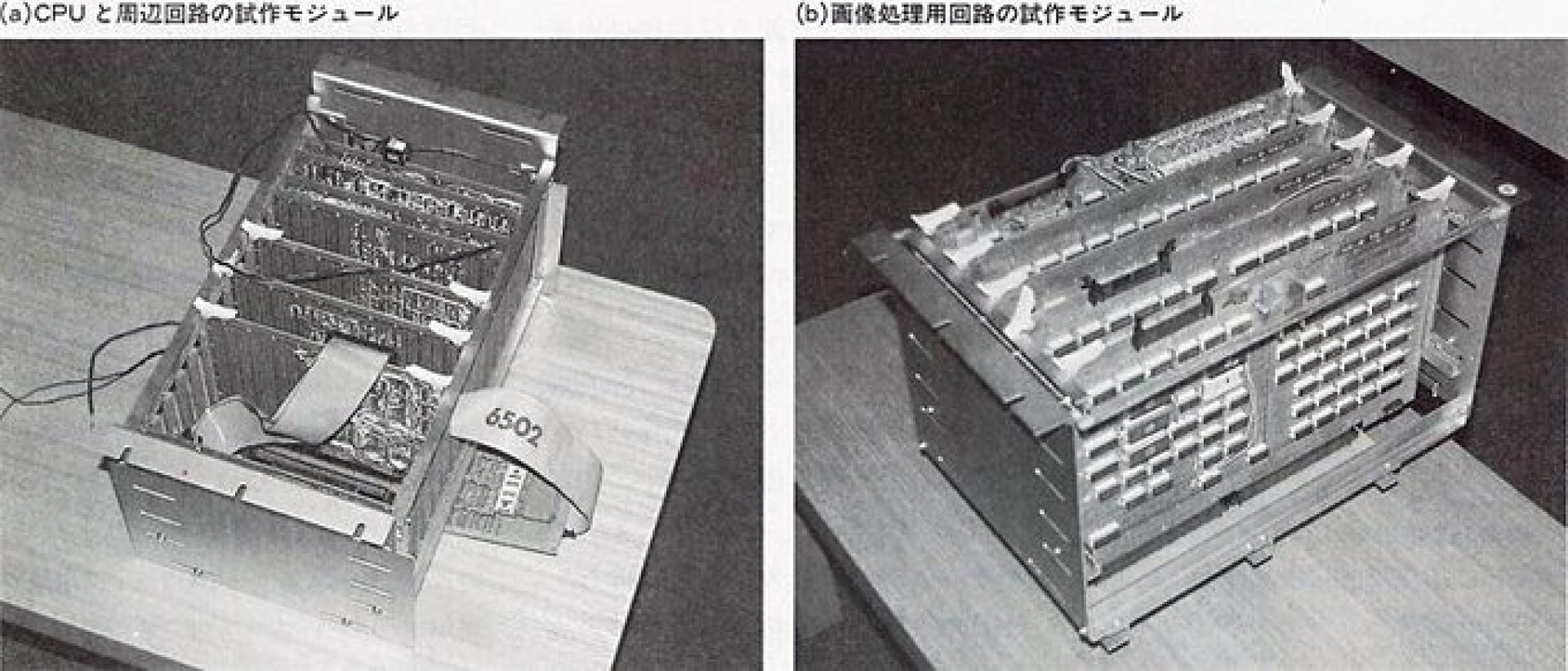

After Nintendo's successful series of arcade games in the early 1980s, they decided to create a home console. The original plan

was to make a 16-bit computer package, including a keyboard and floppy drive. But, then-president of Nintendo Hiroshi Yamauchi

decided the console should be cartridge-based, arguing that keyboards and disk drives would intimidate non-tech-savvy consumers

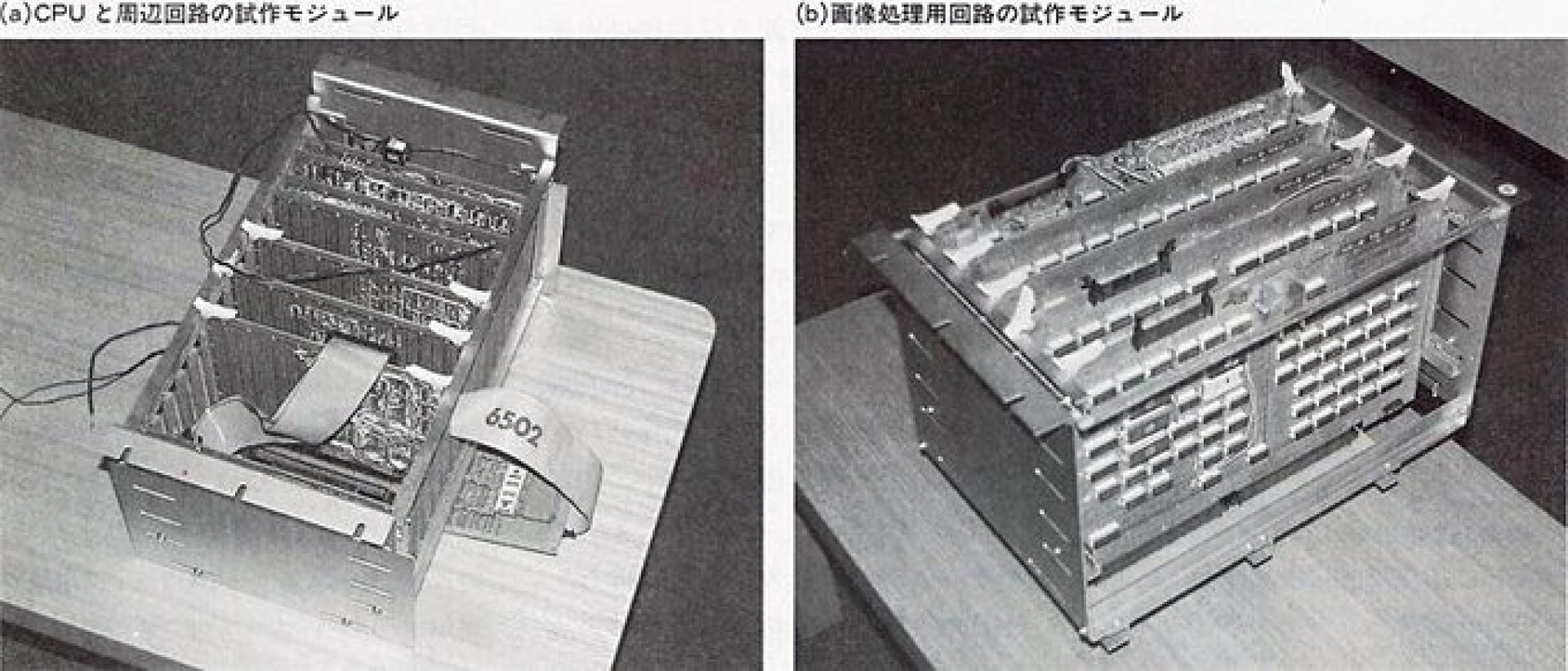

(this revelation wouldn't last). October 1982 saw the creation of a prototype to test the new architecture. This was when

programming tools were created, and games started being coded. The codename for the system was "GameCom" (I beg you not to

confuse this with the handheld), but the wife of head of development Masayuki Uemura suggested it be the Family Computer,

shortened to Famicom.

D-Pad is Mightier

Chief manager of the project Takao Sawano brought a ColecoVision to show to his family. They were amazed by its smooth graphics

compared to that of the slow and flickery Atari 2600. As for controller design, a joystick for movement was planned. But Uemura

felt that kids could step on and break them, so they became flat D-Pads, a consistent controller design for decades to come.

Out of the Pipe

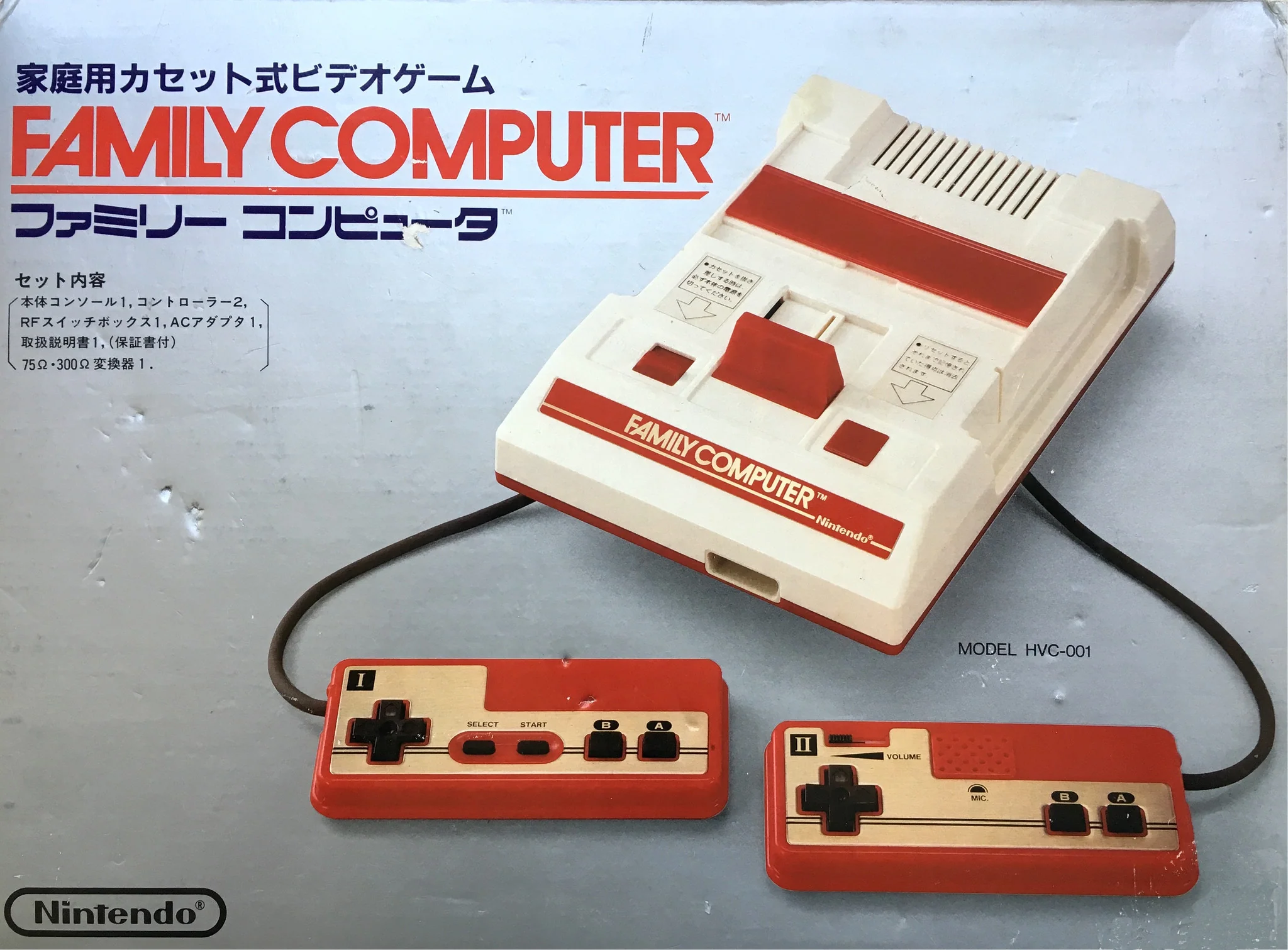

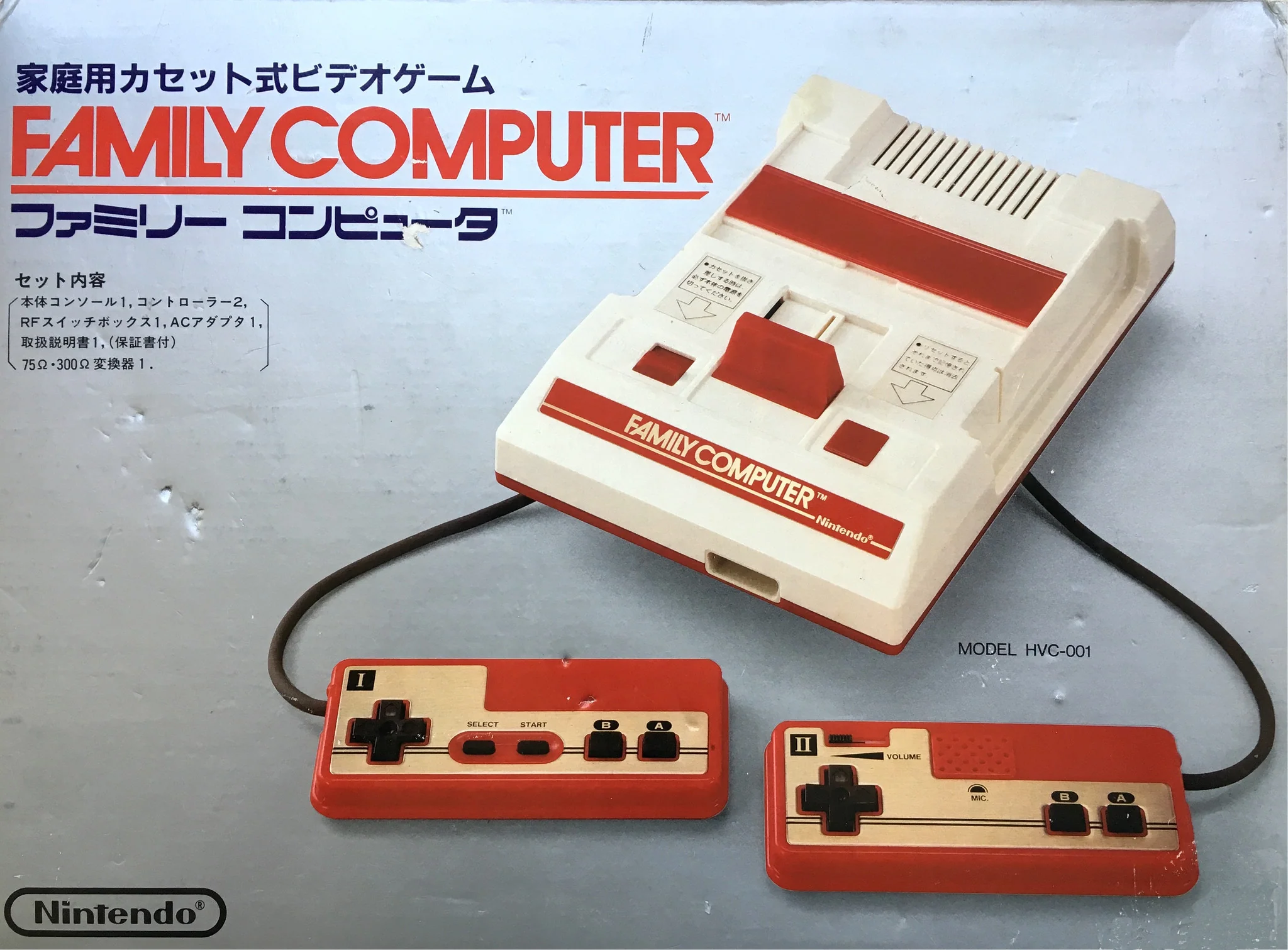

On July 15, 1983, the Famicom was released and was slow to get up to speed. While 500,000 units were sold in the first two months,

some of the first revision units would glitch up and/or crash. The A and B buttons were originally square and made of rubber,

sometimes jamming into the plastic when pressed. Nintendo discovered that faulty circuits were the reason for consoles failing, so

all units sold just before the holidays in 1983 were recalled and production was halted. And although they lost millions of

dollars, they were able to start production back up with those issues fixed. In addition, the second revision Famicom had circular

A and B buttons made of plastic.

Back Out of the Pipe

Despite the setback, Nintendo ended up selling 2,500,000 units by the end of 1984, making it the best-selling game system in

Japan! There would be some accessories made by tech giant Sharp, including a keyboard and cassette recorder released with a

"Family Basic" cartridge.

Western Confrontation

As the Famicom was selling, Nintendo started planning for a North American release. But first, let's survey the region's state of

gaming in 1983. On the home gaming front, the market was plagued by games of varying levels of quality being too similar to one

another, turning consumers and retailers off. This was a prime catalyst for the video game crash, although not the only one. As a

result, Nintendo was forewarned that reintroducing Americans to home video games would be the greatest obstacle yet. With arcade

gaming, the golden age was coming to an end, as people began to lose interest in the games available at the time, causing a decline

in profit. But when conversion kit systems started to arrive, arcades began to bounce back even as people were already going to

them again, but we'll get back to that.

Atari Video Computer System 2?

Nintendo and Atari originally made a deal to release the Famicom under Atari's name as the Advanced Video Gaming System by the end

the year. But at Summer CES, Atari saw Coleco demonstrating their new Adam computer with their ColecoVision console's port of

Donkey Kong. As a result, Atari backed out of the deal at the last minute. But there was a misunderstanding in that while Coleco

licensed Donkey Kong for their ColecoVision, Atari had the license for only home computer ports of the game. The Adam was designed

to be backwards-compatible with the base console's games, and Atari delayed the deal with Nintendo thinking Donkey Kong being

demonstrated on the Adam was a violation Atari's license. The final nail in the coffin for the deal was when their CEO Ray Kassar

was fired.

Continuing development solo, Nintendo decided to introduce their Famicom hardware and games to North America through their own

arcade machine line called the VS. System. It was a big success, selling over 100,000 machines by 1985, due to being affordable and

easy to convert Famicom games to. This gave Nintendo great confidence in getting the hardware and games into American households.

In-comp-nito

Their first plan to reintroduce Americans to video games was to avoid creating a home console altogether, so they revisited a

potential personal computer package called the Advanced Video System. It included controllers and a joystick with infrared wireless

technology, a cassette drive, and even a musical keyboard. The base unit would have a QWERTY keyboard built in like most BASIC-run

computers of the time. When it was shown off at Winter CES 1985, not an order was placed. (Lance Barr put this on display at the

Nintendo World Store in New York City in the mid-2000s! Sadly, it's gone.)

People had little confidence this console would appeal to any retailers. So Nintendo initiated Plan B--marketing it more vaguely as

just an entertainment machine. They started by renaming it the Nintendo Entertainment System. Then, they redesigned it to be

front-loading like a VCR. Famicom designer Masayuki Uemura said in 2020 this also served to prevent shorting something inside the

unit when inserting a cartridge, aggravated by static electricity-laced furniture in dry-climate locations like Arizona.

First Impressions

A highly important aspect of selling a video game is its box/cover art, to depict what the game is about and what the consumer can

expect when they play it. The cover art for most Atari 2600 and Intellivision games, for instance, depicted them as if they were

novels or movies. But obviously, their respective systems were incapable of replicating the art with their graphics. So, the

cartridge labels and boxes for the NES's "black box" games (which there were 30 of from Nintendo that came in black boxes, but 17

were released alongside the console itself) used pictures with in-game sprites on it to represent the game more closely. These

"black box" games were then placed in their own genre. Mario Bros., for instance, is in the Arcade series, and Duck Hunt is in the

Zapper series of games that require the light gun.

Video Toy System

Even specific terminology was used in promotional material and manuals for the console and its games. For example, the formal

"Control Deck" term replaced "console", and "Game Paks" replaced "game cartridges" to market the system to toy stores. The next

issue to tackle was the quality of its games, an issue that killed the industry in the first place. So, Nintendo put strict

stipulations on game releases: Nintendo had to approve each game (hence the "Seal of Quality" on each cartridge) by going through

it and playtesting to determine if it adheres to their guidelines and it's worth playing; Every third-party developer was allowed

to release a certain number of games each year; And one game released on the NES can't come out on another system for two years.

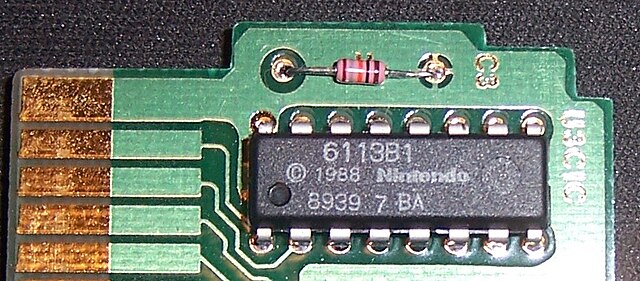

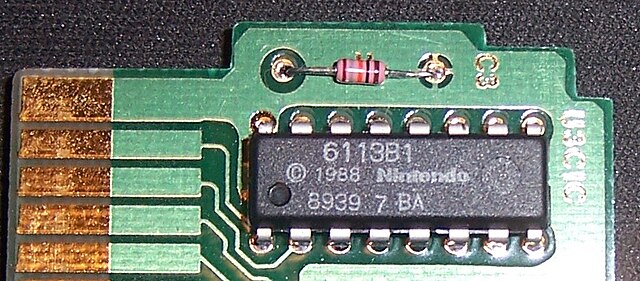

In addition, they prevented pirated and unlicensed games from playing on the NES by implementing a lockout chip in the console and

games that Nintendo licensed. Those without the chip wouldn't play (unless you disassemble the NES, find the chip, and lift a leg

off the board to nullify it).

It more or less worked, until 1988 when companies like Color Dreams and Tengen surfaced to work

around it, which in most cases, ended up tainting the game library a bit. Of course, that doesn't mean all licensed third-party

games were up to snuff.

Finally, to market the system as being way more innovative, a plastic robot called the Robotic Operating Buddy (R.O.B.) was

developed. It communicated with the TV screen by flashing the background blue when a button was pressed. It would control where

and when the robot's arms would move and open or close, making it a pseudo-second player. Sadly, only two games were made

specifically for the Robot series, so R.O.B. was ditched as soon as his purpose to trick consumers into buying a high-tech

entertainment machine was fulfilled.

Game Back On!

Ultimately, it was all a success, and the video game industry was saved! The NES ended up being released on October 18, 1985, and

was a massive success. Its success was what helped Nintendo fully break into American culture and reignited demand in video games

in that region.

The main reason why the NES was so popular back then and is still universally loved by those who were children back in the

console's heyday and younger, newer fans in the retrogaming community today, 40 years after its original release, was the

memorable game library. A bunch of game franchises that exist now were either first established, evolved to its current form, or

made available to a wide audience for the first time did so on the Nintendo Entertainment System, such as, of course, Super Mario,

Castlevania, Mega Man, The Legend of Zelda, and Final Fantasy. Of course, it had a lot of other games that were part of franchises

that have since ended, like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Contra. But the variety made the console one for any gamer to go pick

up in order to find what they like.

Not only did the console give birth to many popular franchises, but it helped start or popularize video game genres that also

reign the industry, such as Kung-Fu and Double Dragon

The console's popularity allowed it to stay in production throughout most of the lifespan of its 16-bit successor, the Super

Nintendo, and through part of the development of ITS successor, known as the Ultra 64 by the time the NES was discontinued in

August 1995. Nintendo offered repairs for it for almost another 15 years before stopping as original parts got more scarce by the

day. Throughout the decade the NES was in production, across all regions and models, the console sold almost 62,000,000 units.

NES Top Loader (NES 2)

Sometimes called the NES 2 (which shan't be confused with the concept sketch of the SNES), the NES Top Loader solved most design

issues the original had. Cartridges were inserted into the top, like most game systems before and contemporary with it, so the

cartridge didn't have to be nudged and poked to work. Shaped and stylized after the SNES, the controllers were redesigned to be

more comfortable in the hands and referred to as "dogbones".

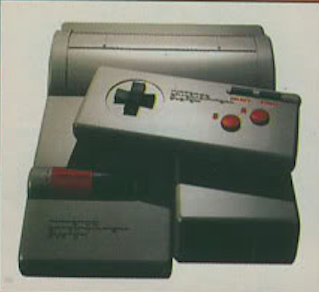

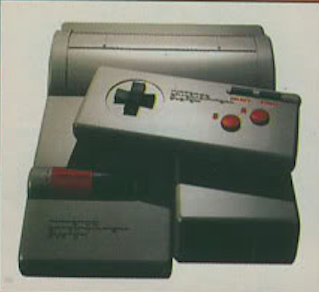

Here's an early version of the NES 2. The console itself remained the same, unlike the controllers. Their start and select

buttons were above A and B, like its older stepbrother original's prototype controllers. The controller was rectangle-shaped,

like the original model. It's also worth mentioning the controller is wireless here.

To solve the blinking power light problem of the original, the 10NES chip that kept region-locked and unlicensed games from

running on the system was ditched. When the Top Loader was released in October 1993, its retail price was $50, way less in

comparison to the original. This new model only came with RF output, which gives an uglier display than AV does. That change was

a cost-cutting measure.

There's two reasons why I think this NES model isn't a good buy, despite the $50 price. First, the time at which it was

released. The original model was marketed as not being a game system, so the purpose was fulfilled pretty much immediately upon

release despite the expense of reliability issues, such as the cartridge input breaking and the blinking light. They should've

phased out the original and brought out the new model a couple years earlier than they did. If the new NES came out in 1989,

when 8-bit games were still standard and after the mega-hit Super Mario Bros. 3 came out, more people may've bought it and

there'd be profits galore. Second, the lack of AV video output on this model. Although RF was cheaper, it was a less desirable

video output that was used by less 16-bit systems than 8-bit. They surely knew this when they released the AV-only Famicom model

two months later in Japan, yet they still gave the US the cheaper one.

This is another shot of the NES 2 prototype. Unlike the last picture, the controller has a wire. Maybe they were toying with

the concept of wireless controllers on this model too?

Sometimes called the NES 2 (which shan't be confused with the concept sketch of the SNES), the NES Top Loader solved most design

issues the original had. Cartridges were inserted into the top, like most game systems before and contemporary with it, so the

cartridge didn't have to be nudged and poked to work. Shaped and stylized after the SNES, the controllers were redesigned to be

more comfortable in the hands and referred to as "dogbones".

Sometimes called the NES 2 (which shan't be confused with the concept sketch of the SNES), the NES Top Loader solved most design

issues the original had. Cartridges were inserted into the top, like most game systems before and contemporary with it, so the

cartridge didn't have to be nudged and poked to work. Shaped and stylized after the SNES, the controllers were redesigned to be

more comfortable in the hands and referred to as "dogbones".

This is another shot of the NES 2 prototype. Unlike the last picture, the controller has a wire. Maybe they were toying with

the concept of wireless controllers on this model too?

This is another shot of the NES 2 prototype. Unlike the last picture, the controller has a wire. Maybe they were toying with

the concept of wireless controllers on this model too?

Now this console is a mystery to me. It was shown to the public alongside the first prototype of the Super Famicom on November 21,

1988 called the "Super Famicom Adaptor", and in an issue of the "Famicom Tsushin Magazine". They disclose that the main 16-bit

console has no backwards compatibility with 8-bit games.

Now this console is a mystery to me. It was shown to the public alongside the first prototype of the Super Famicom on November 21,

1988 called the "Super Famicom Adaptor", and in an issue of the "Famicom Tsushin Magazine". They disclose that the main 16-bit

console has no backwards compatibility with 8-bit games.